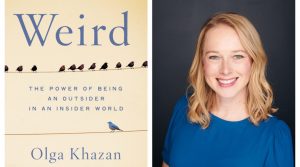

I’ve just finished a fascinating book by Olga Khazan, “Weird: The Power of Being An Outsider In An Insider World.”

Having immigrated to the US as a child and growing up in a very conservative small Texas town, Khazan knows what it’s like to be an outsider and uses her life experiences to introduce us to other people who were unique in their environments. She writes about Michael, who was told his height (4’3″) was a barrier to becoming a doctor. There’s Todd, who didn’t quite fit in at a predominantly Christian elementary school because he was half Jewish. And Julia, one of only a few women to pursue a career as a NASCAR driver.

Khazan writes about how they adapted — or didn’t — and how being different drove their pursuits of alternative paths to happiness. In some cases, that meant moving to new places (e.g. an Amish girl who left the sect). In others, it meant playing along with the mainstream for a while before letting their weirdness fly. For the latter, she discusses a nonconformist survival mechanism called “idiosyncrasy credits.”

If an outsider yearns to be accepted by a group without surrendering their individuality, idiosyncrasy credits are the way to do it. The idea was pioneered by psychologist Edwin Hollander in the 1950s. By studying the way people interact in groups, Hollander theorized that newcomers to a group are better accepted if they first pay homage to its established values and goals, then start to deviate in small ways. At first, conform; then innovate.

This strategy worked for no less than the Beatles…. In the late 1950s, most of the top British performers had antiseptic images and the nascent Beatles were considered too wild. During those infamous nights in Hamburg during which they racked up their 10,000 hours of practice, the Beatles would taunt the crowd and call them Nazis.

Beatles manager Brian Epstein wanted to clean up the band’s reputation. In order to help the band accrue idiosyncrasy credits, Epstein lay down some ground rules: They were no longer allowed to drink or swear on stage. They were to wear suits instead of leather jackets, and bow at the end of each song. Ringo had to promise to shave off his beard and always comb his hair forward. Most egregiously, John Lennon was told to avoid mentioning publicly that he was married to Cynthia Powell and had a child on the way. As Lennon described, somewhat resentfully, years later: “All the rough edges were being knocked off us.” Still the strategy was effective. Bookings picked up, and within months they had a contract and a hit single, “Love Me Do.”

At the height of their fame, in 1966, the Beatles began spending all those idiosyncrasy credits. They dispensed with their polished haircuts and embarked on unusual solo projects. Their music changed, too. According to Ian Inglis’ analysis, 91% of the Beatles’ work before 1966 consisted of love songs; starting with “Revolver,” just 16% did. Through their seamless conformity, the Beatles had become so popular, they didn’t need to be conventional anymore.

Khazan, a contributor to The Atlantic, is a terrific writer and does a nice job weaving her own tales of weirdness with those of other subjects. Having experienced long periods as an outsider myself, I found myself relating to several of the people and the psychological impact of their circumstances.

The mark of a good book is often the disappointment that comes with finishing it, which was the case for me with “Weird” — I wanted to read more.