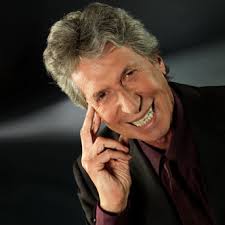

I was sorry to hear about the death this weekend of comedian David Brenner at age 78. I hadn’t seen him work in a very long time, but at the height of his career in the 1970s and 1980s, he was among the funniest storytellers in America. He was part of the wave of comedians who took the observational style created by Robert Klein, George Carlin, and Richard Pryor and adapted it for the next generation, which included Richard Lewis, Freddie Prinze, and Gabe Kaplan.

He made hundreds of TV appearances, but the only time I saw him in person was at the Bushnell Auditorium in Hartford, Connecticut, around 1984. At the time, I was the morning guy at WHCN, the leading rock radio station in town. The cool thing to wear in those days was a satin jacket. Ours were green, with the station’s logo on them, and we wore them to every public appearance. That’s how I had dressed when I’d introduced other comedians at the Bushnell, including Gallagher and Steve Landesberg, so it was only natural that I wore it the night Brenner came to town.

I got there a half-hour before showtime, went backstage, and introduced myself. He sat casually in a button-down denim shirt and jeans as we chatted in his dressing room. About ten minutes before showtime, he excused himself to get ready while I went off to talk to the promoter and see which upcoming events he wanted me to mention onstage. When the house lights went down, I stepped through the curtain into the spotlight, welcomed the crowd, plugged my show and the radio station, and made the obligatory announcements. There was no other comedian as an opening act, so I finished by introducing Brenner to a large ovation.

When I turned to see him come through the curtain with his hand extended to shake mine, I was shocked. Not at the gesture, but because he was wearing a tuxedo. The only times I’d seen a comedian in a tuxedo was on the televised Dean Martin roasts, and all of them were over 60 years old. But Brenner was a class act, and a suit wasn’t good enough for a venue like this. He treated the Bushnell as if it were the biggest showroom in Las Vegas, or a Broadway stage. I felt like a schmuck in my satin jacket compared to him.

He then proceeded to do a 90-minute monologue that weaved story upon story. Having only seen him in short bursts on Carson or other talk shows, I laughed a lot but was also mesmerized at how thoughts seemed to occur to him that sent him on a tangent from one story to another, as if he were drawing concentric circles of comedy. What really amazed me was how Brenner wound his way back from each story to its predecessor, until he somehow returned to the one he had started the evening with. The rest of the crowd was as delighted and thrilled as I was to have taken that joke-filled journey, and we all leapt to our feet in appreciation as he said good night. He wasn’t just classy, but a master of the art.

A couple of years later, Brenner got a syndicated late-night TV show called “Nightlife,” which he used as a platform to feature up-and-coming comedians. He was well-known in the comedy community as a supporter and mentor to many other comics, but the show only lasted one season. The only thing I remember about “Nightlife” is that Brenner hired one of my childhood radio heroes, the legendary New York disc jockey and voiceover talent Dan Ingram as his announcer.

Not long after, Brenner cut down on his touring in order to stay home and fight for custody of his two sons. He lost some valuable career years until making a comeback with a live HBO show in 2000, but by then the business had changed and his style seemed almost old-fashioned because the next generation of comedians, including Jerry Seinfeld, has changed the industry again.

Still, David Brenner deserves a place in the comedy pantheon, alongside the other greats. He’s the one in the tuxedo.