My knowledge of classical music is equivalent to what I know about art: practically nothing. Oh, I can name a bunch of composers — all white men who have been dead more than a century — and even identify a half-dozen of their works by ear. But I don’t know a Mozart symphony from a Grieg concerto or some Mendelssohn composition. As with paintings in museums, all I know is whether or not I like them.

On Friday, my wife and I attended a performance by the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra (one of the best in the country, I’m told). We’ve gone to a few over this season and, in an effort to learn about the form, I always try to read the notes in the program. This time, in the Listening Guide section for the opening piece, Robert Schumann’s Manfred Overture (that’s Opus 115, as you well know), Martin Geck, who wrote a biography of Schumann, was quoted:

Geck observes how wonderfully the music mirrors the “inner conflict” of the protagonist “between heroic bombast, his desire for love, and a sense of profound depression.” The motifs are “torn apart, expanded, and woven together again” in a way that replicates Manfred’s “complex state of mind.”

Well, I listened to the entire overture and didn’t get any of that. Don’t get me wrong. I enjoyed it. But if it were up to me, the program note would have read:

This one has TWO bassoons!

As I watched these great professional musicians doing their jobs, I couldn’t help thinking about all the times their parents had to drive them to lessons, then nag them to practice at home. I mean, even the best of them, on some days, would rather have done something besides rehearse a number for the fifth grade concert, right?

Even with all of their experience, there must be occasions when someone hits the wrong note. Do the other musicians notice? I imagine the second clarinetist catching up to the third clarinetist afterwards and saying, “Hey, Lenny, you blew it on bar 153 when you had your ring finger up instead of down!” With a couple of dozen violinists playing simultaneously, does Suki ever go to the conductor, saying, “Hey, Maestro, Diane over here wasn’t really playing — she was string-syncing it!”

In each section of the orchestra, the best players are towards the front, but at some point, I’m guessing seniority plays a role in the seating plan. Is that the only way to move forward? Does Phyllis have to die for Janet to move up from eighth cellist to seventh?

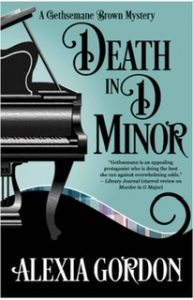

Hey, I think I have an idea for a murder mystery: “Death In D Minor.” Get Netflix on the phone.

There are a couple of instruments I think I could play with minimal instruction, mostly in the percussion section. After all, how hard can it be to hit the tympani or the triangle? Having said that, I’d be the idiot who lost my place during a long lull and hit the giant bass drum with a big flourish at exactly the wrong time, ruining it for everyone.

Finally, I have two tips for attending a classical concert. First, don’t sit close, because you won’t be able to see the whole orchestra — like sitting in the first row of a football game, you’ll have no perspective on what everyone’s doing.

Second, no matter how much you enjoy the performance, don’t clap immediately. Just because the musicians stop playing doesn’t mean the whole piece is over. It might just be the end of the movement. Instead, do what I always do: take a second to consider how the motif was torn apart, expanded, and woven together again.

Then, if you notice everyone else applauding, go ahead and join right in.

[Note: reader Robert Beaton tells me there’s already a murder mystery novel entitled “Death In D Minor,” written by his friend Alexia Gordon. Cancel the call to Netflix!]