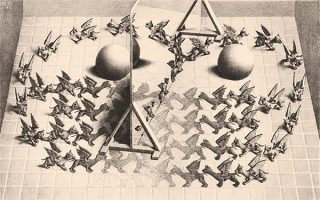

When I was in high school, I became a big fan of the artist MC Escher who, for fifty years, had produced some of the most dazzling drawings I’d ever seen. His work was precise, mathematical, clever, witty, and transfixing. I bought a couple of posters of his most famous pieces and stared at them for hours. My parents bought me a book with even more products of his imagination, and I loved it.

This weekend, Martha and I went to an MC Escher exhibit at the St. Louis Chess Hall Of Fame. In addition to his more mind-bending works, it includes self-portraits, landscape sketches from his time in Italy, and original wood cuts from his collection. From water that seems to travel uphill, to impossible stairs, to tessalations (a word I’d never have known if not for him) of lizards or birds or fish, the man’s genius is on full display.

The exhibit is free and will be in town until September 22, 2019. I urge you to take a look.

That same day, we went to the Missouri History Museum, now home to a traveling exhibit of Pulitzer Prize-winning photographs from the last seven decades. The collection covers joyous celebrations, natural disasters, and a lot of wars. Each time I came upon one of the latter, I could only think of the waste of human lives, often at the hands of brutal leaderships or because of power plays or political miscalculations.

Each photo is accompanied by text putting it in historical perspective. Next to Joe Rosenthal’s famous photo of the Marines raising the US flag at Mt. Suribachi is the detail on how many thousands of Americans and Japanese died on that island in the Pacific. Next to Nick Ut’s iconic photo of a 9-year-old Vietnamese girl running down a road, her clothes burned off by a napalm attack, is the story of how editors had to put aside their ban on publishing nude photos to show the public the true horror of war. Then there’s Ken Geiger’s photo of the Nigerian relay team, thrilled to have won a bronze medal at the Barcelona Olympics.

Another thing that struck me is that many of those captions describe the photojournalist hearing or seeing something and being drawn to it. In many cases, they literally ran in the direction of danger, hoping to capture for posterity a tragedy unfolding or a life being changed forever.

The Pulitzer Prize photographs exhibit (also free) will be in St. Louis until January 20, 2020.

One caveat, though: at the entrance to the exhibit is a sign warning of how intense many of these pictures are, and urging parents to view it first without their children to gauge whether it’s appropriate for younger eyes. Of course, many people ignore the sign. As we were walking out, we were passed by one father who was walking in with his probably-eight-year-old daughter, telling her excitedly they were going to “see some pretty pictures.”

Shame on him. There are many words that describe the photos in that room, but “pretty” is not one of them. His daughter is probably still having nightmares over what she witnessed that day.