For a long time, I’ve wondered how songwriters know when a tune is done, when it reaches its completed form. They’ve composed the music, written the lyrics, decided on instrumentation, used studio tricks to enhance their vision for the song, and probably changed each of those elements several times over in the process.

But what makes them say, “That’s it, we’re done”?

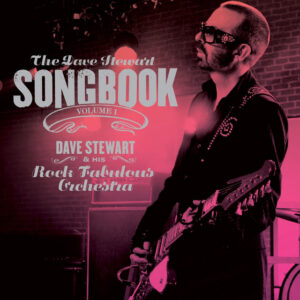

I’m thinking about this again as I listen to The Dave Stewart Songbook, a 2008 compilation of things he wrote, co-wrote, or co-produced, many of which were hits. Of course there are Eurythmics songs (“Sweet Dreams,” “Here Comes The Rain,” and “Missionary Man”), but also ditties originally released by Sinead O’Connor, No Doubt, Céline Dion, Bon Jovi, Sarah McLachlan, and Tom Petty’s “Don’t Come Around Here No More.”

But the album does not consist of the original versions. They are tracks he re-recorded with a group of musicians and singers he called the Rock Fabulous Orchestra — and they sound different, with changes in instrumentation, tempo, and style. In other words, the songs were reimagined. That also raises the question of whether it’s a cover version when the original artist records a new take on their own work.

Bruce Springsteen has changed the timing and tempo of some of his classics (e.g. acoustic versions of “Born To Run” and “Thunder Road”) when performing them live. In college, I heard the Grateful Dead do a very slowed-down “Friend Of The Devil” in concert. Lots of other musicians have done it, too, perhaps because they got sick of doing them the same way over and over for years or decades.

Every radio show I hosted was live, so there was no possibility of an alternate take — whatever came out of my mouth into your ears was the final version. So were my newspaper op-eds and TV commentary, all produced with strict deadlines. Once broadcast or printed, there was no mechanism for revision. The same goes for art — once Van Gogh sold his work in what he deemed its final form, he never woke up a week later and asked the new owners if he could add a few more brushstrokes.

On the other hand, I have written thousands of items for this website over a quarter of a century, and there have been several occasions where I went back years later and did some polishing. Perhaps a reference seemed too dated, or I didn’t like the phrasing or syntax, or I thought of something I wanted to add. Clicking the Publish button meant it was ready for public consumption, but not necessarily finished in perpetuity.

Neil Simon kept monkeying around with some of his most famous works, like turning Oscar and Felix into Olive and Florence for a female version of “The Odd Couple.” Such changes always seem like desperation to me, an attempt by a creative person to wring a few more dollars out of their work. But in doing so, they cheapen it.

It happens to movies, too. We’ve all heard of a Director’s Cut. I’ve lost track of how many times Francis Ford Coppola has needlessly messed around with the various elements of his “Godfather” trilogy. There was controversy several years ago when Zack Snyder had to step down as director of “Justice League” because of a family tragedy and the film was finished by Joss Whedon, who added and removed some elements Snyder had shot. But when that was released, it bombed, and fans demanded to see the Snyder Cut. Warner Brothers relented and allowed him to spend tens of millions of dollars to complete his original version.

So, at what point are creative projects done?