Most Americans think Jackie Robinson was the first Black man to play baseball on a team with white players. In fact, there were integrated professional baseball teams in the decades after the Civil War. But by the early 1900s, Jim Crow laws and the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson “separate but equal” decision forced those teams to go monochromatic. That’s when the first Negro League teams were born.

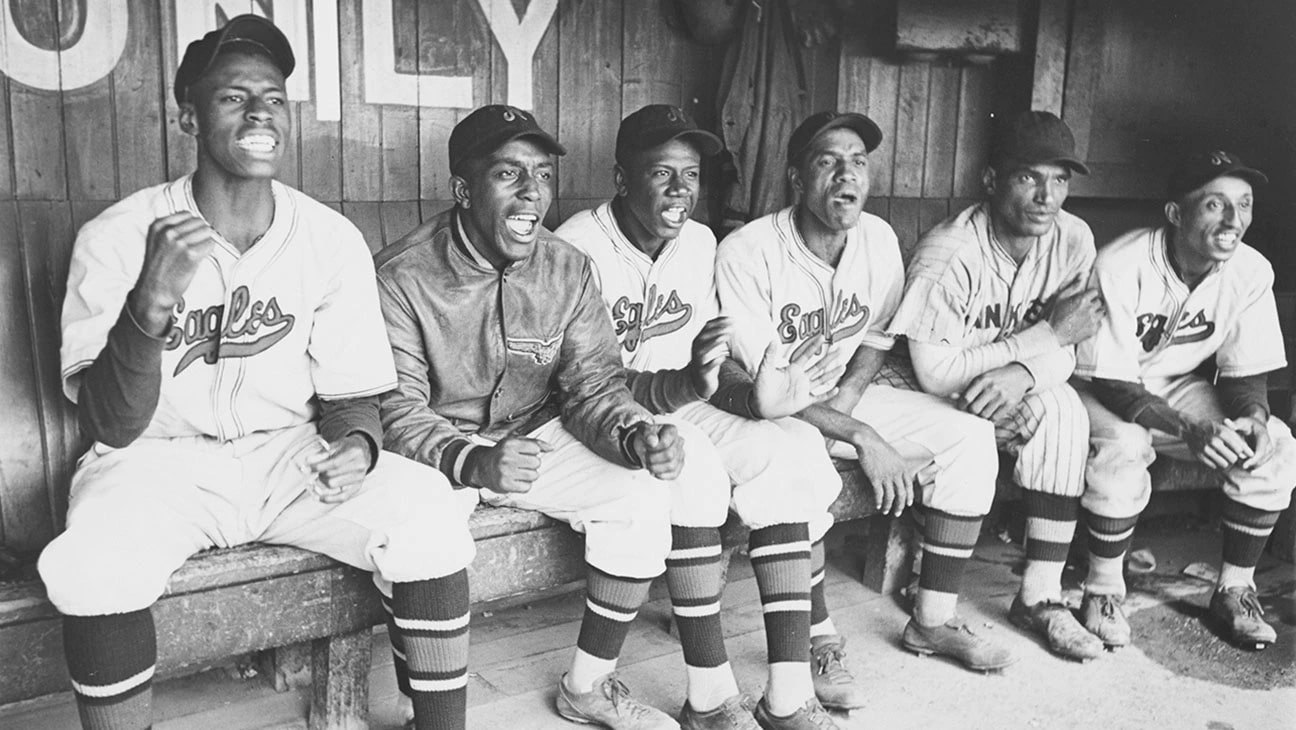

I learned this fact from “The League,” Sam Pollard’s new documentary tracing the history of the players, owners, and teams like the Kansas City Monarchs, the Homestead Grays, and the Newark Eagles. Pollard dug up archival film footage, still photos, and audio clips to tell the story of the rosters and personalities that thrived over the course of the next four decades, including legendary pitcher Satchel Paige, home run king Josh Gibson, fielding wizard Buck O’Neil, and many more. Also heard and seen in the documentary are Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Monte Irvin, along with Larry Doby (first Black player in the American League). Robinson’s widow, Rachel, explains how Jackie had to repeatedly turn the other cheek when white fans and sportswriters hurled vicious racist epithets at him on and off the field.

There’s also discussion of teams barnstorming across the country — sometimes playing three or four games in a single day — and how differently the players were treated when they played winter ball in Puerto Rico and elsewhere in the Caribbean, where their skin color was not an impediment to their daily lives.

Particularly compelling was a section about Effa Manley, the only woman to be inducted into the Baseball Hall Of Fame. As co-owner of the Newark Eagles, she was instrumental in using her position to better the Black community and the early civil rights movement. It’s through her that I learned that Branch Rickey, who broke the color barrier by hiring Robinson, refused to compensate the Negro League team he was under contract to. Other Major League owners followed his lead, and as the best Black talent moved to the majors, the teams they left behind struggled financially before disbanding.

At its peak, the Negro League was so popular that churches would move the time of their services to an hour earlier on Sunday morning so parishioners could get to the ballparks in time for games. When the Negro League was eventually dissolved because its fans could now see their favorite players on the majority-white teams, it had the unintended consequence of hurting other Black-owned businesses and employees, some of whom never rebounded.

In his previous documentaries, Pollard compiled memorable tributes to Arthur Ashe, Sammy Davis Jr. (which I discussed with him in 2017), and Bill Russell (which I reviewed earlier this year). “The League” stands alongside them as another well-told deep-dive into a part of American history some of us thought we already knew. I say that having visited the Negro Leagues Museum, whose president, Bob Kendrick, appears on camera in the documentary, as well. If you’re ever in Kansas City, it’s worth seeing, along with the American Jazz Museum next door.

I give “The League” an 8.5 out of 10. Available now on several video on demand platforms.