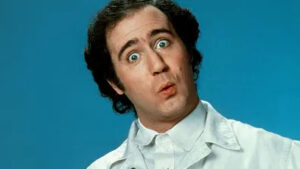

On the 40th anniversary of Andy Kaufman’s death, here’s a piece I wrote about him in 2000 explaining why I was not a fan…

In case you haven’t noticed, the media has pronounced this Andy Kaufman Month. They’re all caught up in the hype of “Man On The Moon,” the movie starring Jim Carrey as Kaufman which opens this week, and the two bios of him which have been published within the last month.

Show business is well-known for its lack of perspective, particularly on stardom. Yet even by its own ridiculous standards, the plaudits for Andy Kaufman are beyond all reason. They include phrases like “changed the face of comedy forever,” “splendidly surreal,” and the used-so-often-it’s-now-completely-deflated “comedy genius.”

Rarely does anyone refer to Andy Kaufman as what he truly was: a nutcase who was over-indulged by Hollywood and the rest of show business. It is precisely that over-indulgence which I find most amazing.

Don’t get me wrong. I thought some of what he did was amusing. I smiled at the Mighty Mouse bit. I smirked at the Foreign-Man-Becomes-Elvis impersonation. They were not hysterical nor the most ground-breaking comedy I’ve ever seen. But if you listen to the praise being heaped on Kaufman now, you’d think that he was the most fantastic entertainer to ever live. He wasn’t that, but he was certainly among the most coddled and spoiled.

Selective memory is an amazing thing. The cast of “Taxi,” on which he played Latka Gravas, unanimously hated him. Yet they all appear in the movie and have recently been quoted saying wondrous things about him. One of the producers marvels at how, in the show’s first season and with no previous sitcom experience, Andy never forgot his lines. What the producer seems to have forgotten is that in the first dozen shows or so, Latka spoke in his own gibberish language that Kaufman had made up! He could have said anything and it would have fit, and no one would have known if he flubbed a line.

What Danny DeVito, Tony Danza, Marilu Henner, and Judd Hirsch aren’t saying now is that, when they were doing “Taxi,” he drove them crazy by showing up late to the set or not showing up at all and getting special treatment from the producers. Kaufman was treated like the star of the show, even though it really revolved around Hirsch’s character. Still, the producers coddled him. At one point, Jeff Conaway became so upset with the way he abused his privileges and was never punished, that he got fed up and went after Kaufman with his fists. Naturally, Conaway was perceived to be the bad guy, because Andy could do no wrong.

The producers even agreed to a contract clause which guaranteed that Kaufman’s obnoxious alter-ego, lounge singer Tony Clifton, be featured in a couple of “Taxi” episodes — a professional arrangement that ended in an on-stage fight culminating with his physical removal from the studio. What other performer would be allowed to continue that kind of nonsense?

In the later seasons, they indulged him even more by allowing Latka to develop a schizoid personality that turned him into other people. Talk about typecasting. These were at the time universally considered to be the lamest episodes the show ever produced. But now, with myopic hindsight, there’s nothing but praise for them.

Kaufman is considered “ground-breaking” because he thought it was more entertaining to go onstage at a comedy club and not be funny. You can see dozens of people doing that regularly at open mike nights across the country. But because he somehow had been knighted as Comedy’s Golden Boy, it was different?

What is entertaining about a guy getting onstage, announcing that he has a growth on the back of his neck, and then letting the audience come up and touch it? The audience, who would have licked his boots if he had asked them, came up one by one and played along. When they were all done, he said thank you and left the stage. You think I’m making that up? Kaufman did that as his entire act on a televised special, and was hailed for it with comments like, “Only Andy Kaufman would have the guts to try something so daring!” In reality, if any other schlub had done it, he would have been shown the door and never invited back. That’s what I mean by over-indulged.

Here’s another example.

For some reason, Kaufman thought it cool to take a job as a busboy at a Hollywood deli that was frequented by the stars. He did the job just as any busboy would, anonymously. But he couldn’t control his obnoxious side. Bill Zehme tells the story in his book (“Lost In The Funhouse”) of the time Richard Gere was having dinner with a friend in the deli. Kaufman noticed him and, staying in busboy character, went over to see if everything was okay. He did this over and over again with the express purpose of annoying Gere enough to get a response. Gere was irritated, but didn’t want to make a scene. Finally, Kaufman took a pot of coffee to the table and started refilling Gere’s cup, but didn’t stop when it was full. He kept pouring, so that the coffee overflowed onto the table and into Gere’s lap. At that point, Gere exploded with anger, as any normal person would. Kaufman was thrilled to have engendered such a reaction. Here’s where the over-indulging comes in. He was not fired or even castigated for this stunt. It was simply written off as one of Andy’s moments of real-life theater, and Gere was made out to be the humorless one for not going along with the joke. Hello?

There was nothing entertaining about Kaufman’s wrestling theatrics either, least of all his bouts with women — which, by the way, were merely a ruse on his part to get women to rub up against him. He was doing it purely for the sexual thrill (he would get so excited onstage that more than once he had to be taped down so that his erection wouldn’t be visible on television). It was the kind of misogyny that even the WWF wouldn’t sink to. Yet Kaufman was over-indulged and allowed to do it on television time and time again. Why?

Oh yeah, because he was a genius.